Navigator’s list of quintessentially Canadian diversions

GIMME SHELTER

CRANBROOK, BRITISH COLUMBIA

Located in the Canadian Rocky Mountains, between Banff and Glacier National Park, this region is ideally suited for activities ranging from horseback riding to river rafting. Stay at the Three Bars Guest Ranch, a dude ranch that creates an authentic rancher experience for guests.

Where to stay

Three Bars Guest Ranch | www.threebarsranch.com

VANCOUVER ISLAND, BRITISH COLUMBIA

Located near Tofino in the Clayoquot Sound UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, Clayoquot Wilderness Resort offers guests a restorative, bespoke, turn-of-the-century outpost camping or “glamping” adventure. This world-class eco-safari-style resort works closely with the Ahousaht First Nation to make the reserve sustainable and accessible for visitors.

Where to stay

Clayoquot Wilderness Resort | www.wildretreat.com

ORILLIA, ONTARIO

If you’re an adult who longs for the days of camp, and you want to get back to basics, try a digital detox at Camp Reset next summer. Enjoy a total break from technology, with camp programming that focuses on wellness, workshops and group activities—all designed to make you feel like a kid again.

Where to stay

Camp Reset | www.campreset.com

NORTH HATLEY, QUEBEC

Founded more than 100 years ago, North Hatley is recognized as one of Quebec’s most beautiful villages. It is home to a number of century-old heritage buildings, one of which is Manoir Hovey, a five-star Relais & Châteaux property that has counted the Clintons among its guests.

Where to stay

Manoir Harvey | www.manoirhovey.com

FOGO ISLAND, NEWFOUNDLAND

Newfoundland and Labrador’s largest offshore island has a long maritime history and a vibrant art scene. While Fogo Island is accessible year round, whale migration and sea-cliff footpaths make the island a perfect destination in the spring.

Where to stay

Fogo Island Inn | www.fogoislandinn.ca

WINNIPEG, MANITOBA

Take an urban getaway to Winnipeg to visit the Canadian Museum for Human Rights’ Tower of Hope, which provides panoramic views of the city. While in “the Peg,” dine at Chef Mandel Hitzer’s internationally acclaimed Deer + Almond. Hitzer, who received attention this year for RAW:almond, his award-winning month-long pop-up restaurant situated on the frozen Assiniboine River, has put Winnipeg on the map for foodies far and wide.

Where to stay

The Mere Hotel | www.merehotel.com

EXTRA TIP

Where to eat

RAW:Almond | www.raw-almond.com

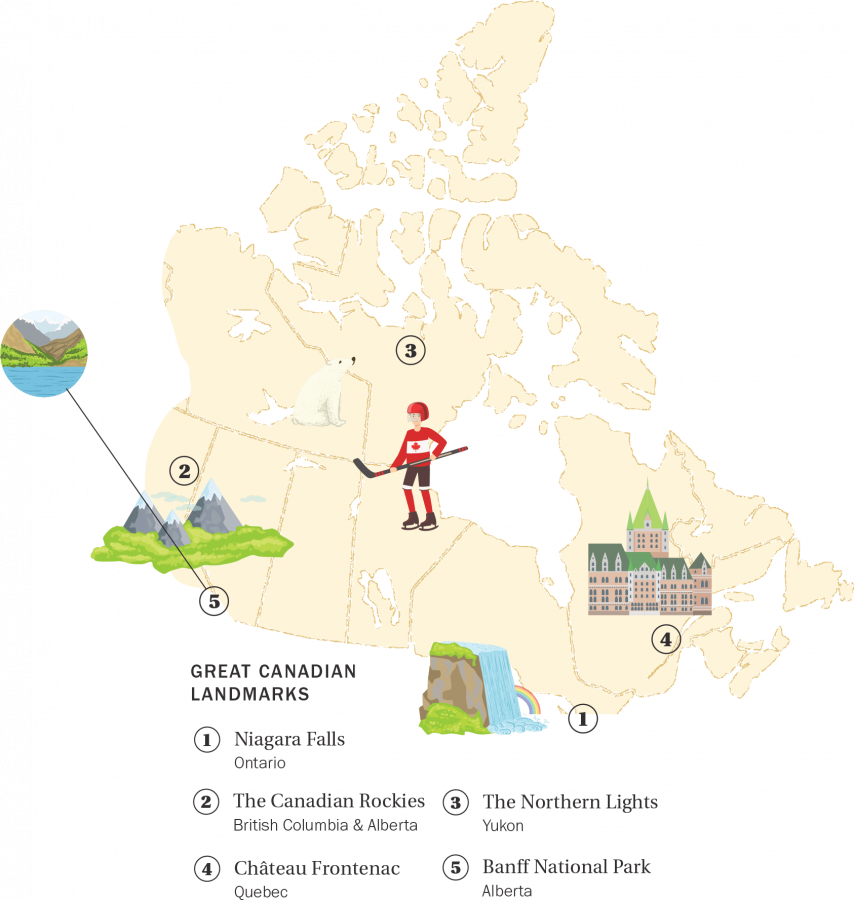

GREAT CANADIAN LANDMARKS

BOOKMARK THIS…

Notable Canadian reads

The Book of Negroes

by Lawrence Hill

Life of Pi

by Yann Martel

Anne of Green Gables

by L.M. Montgomery

Room

by Emma Donoghue

Lullabies for Little Criminals

by Heather O’Neill

The Handmaid’s Tale

by Margaret Atwood

CANADIAN CONTENT

Best Canadian TV shows

Being Erica

Kids in the Hall

Degrassi

Orphan Black

Schitt’s Creek

Heartland

Saving Hope

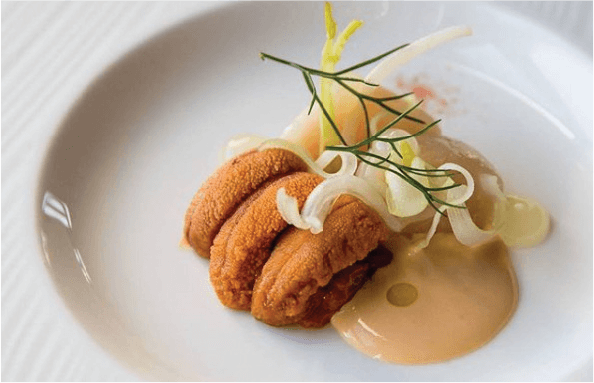

DASHING DINING

Canada’s best dining experiences

LE VIN PAPILLON, Montreal | www.vinpapillon.com

ALO, Toronto | www.alorestaurant.com

DEER + ALMOND, Winnipeg | www.deerandalmond.com

PIGEONHOLE, Calgary | www.pigeonholeyyc.ca

RAYMOND’S, St. John’s | www.raymondsrestaurant.com

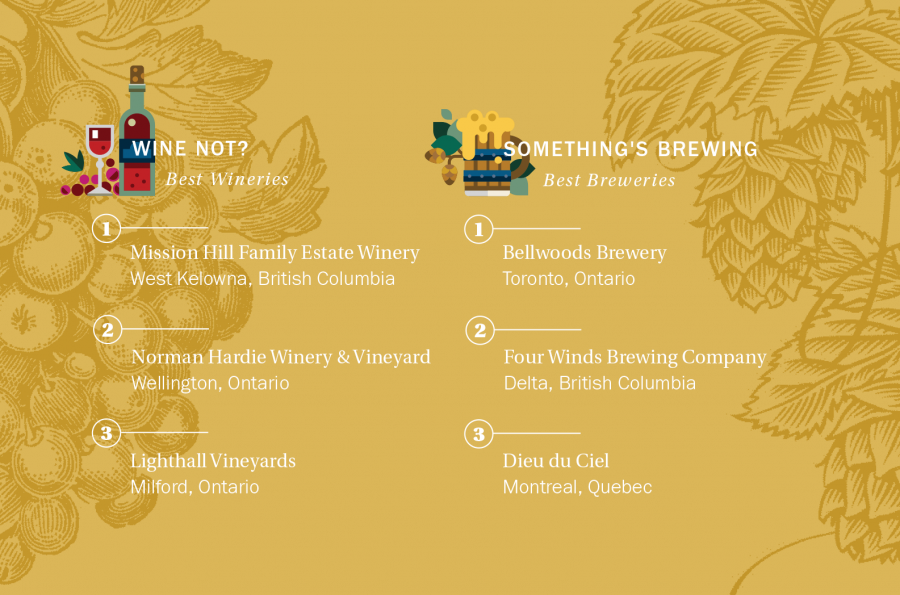

BEST WINERIES – BEST BREWERIES

STRONG & FREE

Here is a list of notable Canadians who have made their mark in 2017 in popular culture, sports, science and art:

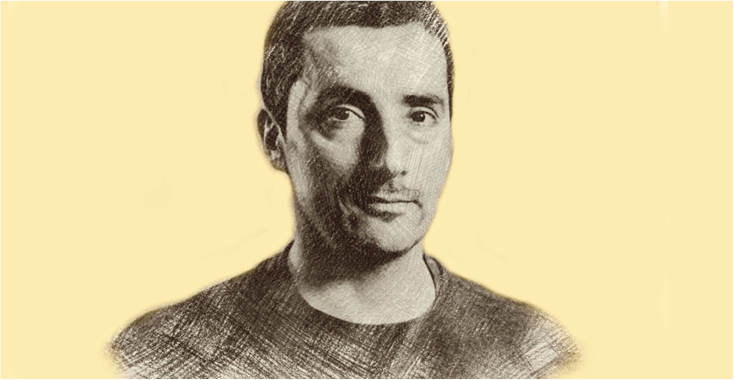

DENIS VILLENEUVE | Canadian film director

French Canadian filmmaker and writer Denis Villeneuve has received international acclaim with his feature films Arrival (2016), Sicario (2015) and Prisoners (2013). Villeneuve’s star continues to rise this year with the release of Blade Runner 2049.

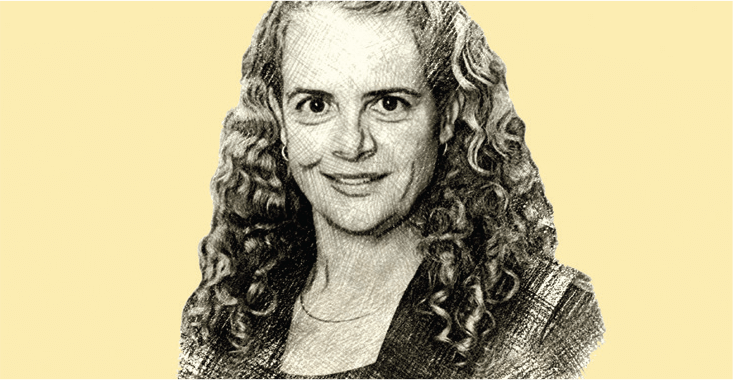

JULIE PAYETTE | Governor General

An engineer, science broadcaster and corporate director, Julie Payette has done everything from being an astronaut to carrying the Olympic flag during the opening ceremonies of the 2010 Vancouver Winter Games. Payette was sworn in as Canada’s 29th governor general on October 2nd.

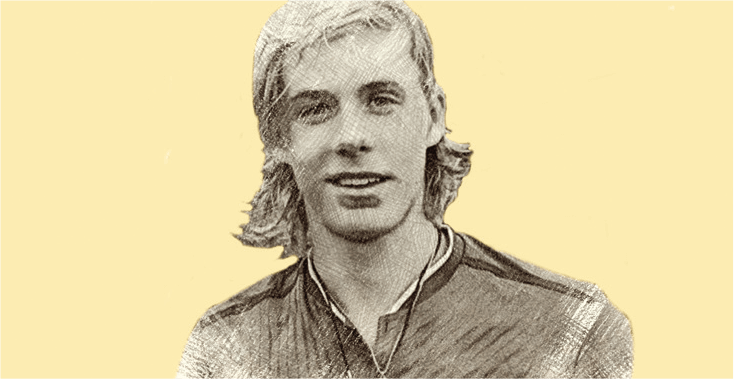

DENIS SHAPOVALOV | Canadian tennis player

Denis Shapovalov is Canada’s newest tennis sensation. After defeating veteran Rafael Nadal in a thrilling third-set tiebreak at this year’s Rogers Cup, and with vocal supporters like hockey great Wayne Gretzky, this 18-year-old seems to have what it takes to be a superstar.

KENT MONKMAN | Canadian artist

Kent Monkman is a Canadian artist of Cree ancestry who drew attention this year with the opening of his exhibit Shame and Prejudice: The Story of Resilience. Monkman’s pieces provide 150 years of perspective into the treatment of Canada’s Indigenous peoples from the beginning of the country’s history. The exhibit will display across Canada until 2020, with stops in Kingston, Charlottetown, Halifax, Montreal, Winnipeg and Vancouver.

SHANIA TWAIN | Canadian singer-songwriter

Everyone’s favourite Canadian pop-country music star is back this year with the release of Now, her first album since 2002. Shania Twain will be hitting the road to promote the album with a 46- date tour scheduled for next year.