The end of Gawker

Last week, Gawker Media announced that it was closing its doors after a protracted legal battle with multibillionaire Peter Thiel, who seems to have made it his mission to destroy the site.

Gawker was a website that pioneered much of the content form and style of online writing we see today. As noted in its closing statement, which included site data, Gawker predates today’s tracking tools, including Google Analytics. Along with its affiliate sites like Deadspin, Jezebel, and Gizmodo, the ‘Gawker Network’popularized the snark and the informal and incisive style that is now characteristic of online writing. As the network’s flagship website, gawker.com was the first to publish posts on topics and from people that, arguably, wouldn’t have found a home otherwise.

As Adrien Chen notes — Gawker was a unique place to become a journalist because it put writers in front of the masses to ‘express themselves how they wanted.’ The site was the birthplace of much of Internet culture. Despite the temporality of the net, and our tendency to valorize something and then dispose of it, Gawker will likely live on as a legend, if for no other reason than the fact that most of its writing staff have gone on to other sites and publications to continue publishing content that perpetuates, in some way shape or form, the style originated by the site.

Gawker was generally the first in any situation to point out when companies, publications, and people — particularly people of power or influence — were being self-congratulatory, smug, or overly-indulgent. Gawker was also a pioneer in the comments section, which was one of the draws to the site. It created the kinja discussion thread, which is pretty similar to how comments and replies currently work on Facebook posts. It was ahead of its time. You can still see it in action on Gawker’s affiliated sites. It really attempted to create an online discussion between bloggers, writers, journalists, and commenters and this worked (or didn’t) to varying degrees throughout the site’s history.

Online conversations and commentary on any given issue can feel circular, and we often feel like everyone on a particular social media platform is all talking about the same thing. Recently, NPR decided to shut down the comments section on its site for partly the same reason: in July, of the 22 million unique users to the site, they had 491,000 comments. Those comments came from 19,400 commenters, or 0.06% of users commenting. Whatever discussion its posts were generating; it was amongst the same group of people.

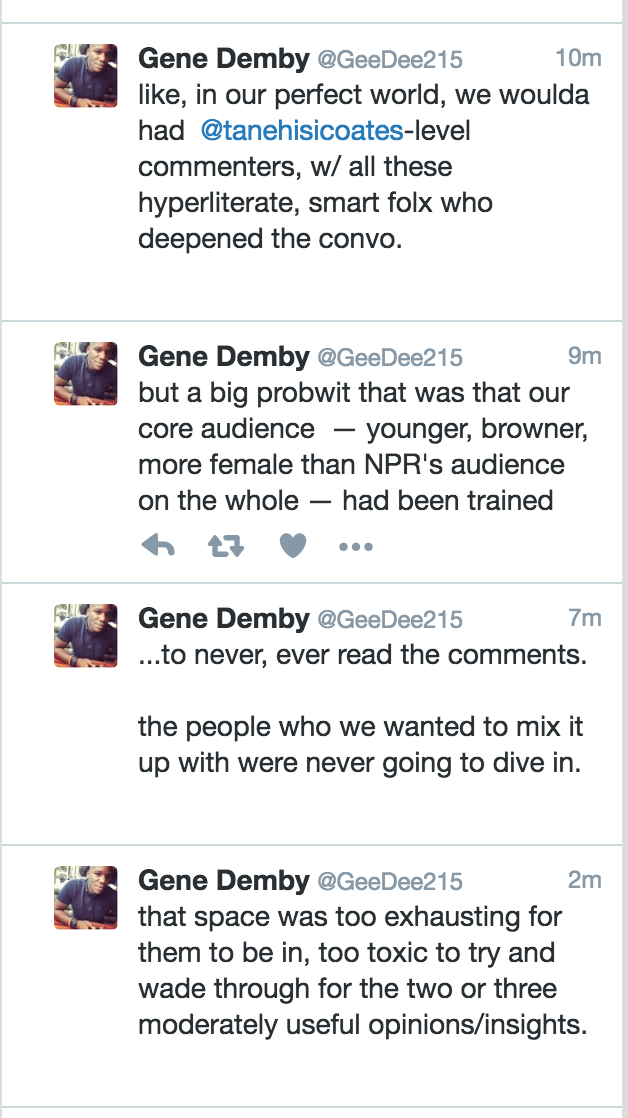

But, just as in life, not all social spaces are created equal. On Twitter, Gene Demby, a writer at PostBougie and NPR’s Code Switch explained the trouble with comments sections and why it’s difficult to make them resemble anything constructive:

So in the wake of Gawker’s demise and NPR removing its comments section, it seems fitting to look at some of the trends of our particular social spaces. Public online spaces of interaction can be exhausting or potentially harmful for some people — mostly minority groups. But what about the areas we think of as being more ‘private’, or at the very least limited by permissions and friend requests?

Real friends — how many of us?

In June, Facebook retooled its algorithm to show more posts from your friends over media outlets in your news feed. Not only that, but it reportedly prioritizes the content from friends that you care about — aka the people you interact with most on the site. Facebook used to limit the number of posts you would see in a row from the same person. However, with this new update, this rule is less stringent, allowing your friends to dominate your news feed more than ever.

But, the truth is, Facebook is no longer an accurate representation of your social circle. Most of us don’t talk to 300 plus people a day, let alone probe them on their political and moral beliefs. However, it seems that more than any other platform, Facebook has become the platform for moralizing or politicizing. Facebook is at once, both personal and public, which means publicizing your views on topics that could be considered sensitive or controversial is safe and scary in equal measure.

Self-care

In many ways ‘Self-care’ is the Internet term of 2016. To be short about it — the year has felt bad. World-falling-apart-at-the-seams kind of bad. In case you’ve somehow forgotten, the year has been filled with terrorist attacks, police brutality, peaceful protests-turned-violent-attacks, unsavory politics, and a myriad of other now seemingly regular disasters. For many, social media has, if not perpetuated, at the least amplified, the feeling of constant bad news.

Self-care takes different forms. Some feel checking out from social media altogether is necessary — this is also become some face more discrimination and harassment online than others for sharing their views. And as for sharing your political views on Facebook — well, you can’t really make blanket statements for how this does or does not go, because the stakes are incredibly different, depending on who is doing the sharing.

Quartz published a (somewhat sketchy) article on data collected by Rantic, that suggested your political Facebook posts do not alter people’s behavior or views. The authenticity of the study can’t be verified, however, anecdotally, it feels true: most people who post political updates on Facebook are posting to an audience that, by-and-large, already agrees with them, and that these posts are not changing anyone’s political views.

On the flip side, The Ringer explored the mainstreaming of the ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement and the role of social media. Looking at how the hashtag has spread generally, and then rapidly, following horrifying cases of brutality caught on camera, it compares online tipping points of adoption to when Facebook introduced the equals sign as a profile picture option to show support for marriage equality.

To be clear, there are vast differences between expressing your political views in a well-thought out and constructed post detailing your experience or beliefs and changing your profile picture to include a watermark filter that identifies you as an ally to a particular cause or issue. The chasm between replacing your photo with a Facebook-created-and-sanctioned filter and reaching a point of frustration and confusion at systemic and institutional marginalization is miles wide. The Ringer article makes this point, but also suggests that there are crossover lessons.

Based on a study Facebook conducted on the equals sign profile picture, the number of people posting about an issue does have an impact on whether or not you follow suit. The median number for people to change their photo is eight. Once something becomes popular, there’s less social risk associating yourself with the cause — you can change your photo and update your status with impunity, you don’t risk political backlash or losing friends who vehemently disagree with your viewpoint.

Over the past couple of years though, a performative element has become part of the Facebook post/status update/profile picture change. This doesn’t exclude people from posting about causes or social issues they genuinely care about, but the performance and identification are not mutually exclusive. You receive social recognition and validation for said posts, have warm and self-affirming feelings about your beliefs, and are encouraged to post more on a similar topic.

So there is some truth to both sides. Facebook posts may not alter behavior, but they can grant people who would not take the initiative to post of their own volition permission to enter a digital and social space. Depending on the issue, commenting on social media can be in direct opposition to someone’s sense of self-care — or to put it another way, posting your political views on social media requires you to assess your level of comfort and safety within your online network, the same way it does in a real-life social setting. Studies that look at whether or not issues are adopted are operating on the assumption that all issues are created equal — or can be responded to with equal weight. Depending on the topic, people discussing an issue might not be the ones who are impacted the most. For some of these people, the political and personal blowback you can experience from engaging online isn’t worth the trouble.

And also, from those who are discussing a politically or socially sensitive topic, there’s a line — sometimes, identifying yourself as an ally to a given cause can come off as more congratulatory than not. Like when someone feels the need to tell you about the nice thing they did or are planning on doing for you, rather than just simply doing it, it can feel like cashing in on social justice credit.

#woke

There’s a whole segment of the population that doesn’t know what being woke is — which is an interesting phenomenon, because woke is now common enough to start turning back, almost full circle, to perform double duty as both a positive and negative term. As The New York Times stated in April, ‘Think of ‘woke’ as the inverse of ‘politically correct.’ If ‘P.C.’ is a taunt from the right, a way of calling out hypersensitivity in political discourse, then ‘woke is a back-pat from the left, a way of affirming the sensitive.’ More to the point than that even, ‘It means wanting to be considered correct, and wanting everyone to know just how correct you are.’

Although being woke is becoming a casualty of Internet performance, its origins are in black rights movements and essentially means being aware of the various complexities and problems which our society functions, the multiplicity of ways in which systematic racism and prejudice manifest, and refusing to accept them as the status quo. Its popularization is usually attributed to Erykah Badu, who urged people to ‘stay woke’ in her song ‘Master Teachers’ in 2008. Today, it can still mean that, but it can also mean that you’re so woke you haven’t slept in days, what with pointing out all the ways in which you are more awake to the various injustices in the world than everyone else. In the negative context, being woke is not only performative, but condescending and competitive.

Woke friends — in the negative sense — usually beget woke friends because woke users are generally very active on social media, in order to prove their wokeness, as public recognition is a core component. As an insult, woke is more popular on Twitter, but unaware woke behaviour is arguably more prominent on Facebook. Generally, Twitter is a more public forum: you’re interacting, or at least reading, tweets from people that are writing for a larger and more public audience than on Facebook. Therefore, Twitter users are quicker to point out this kind of behaviour in one another and you’re less likely to find the kind of affirmation you would from your friends.

The rules of engagement

Basically, this is all a word to the wise and consideration for your online objectives. If our social networks are generally comprised of people with similar political views and online discussions are usually dominated by a few, spreading messages and garnering support requires a tipping point for it to spread to a wider audience. But what that looks like and how that works is dependent on your audience and your issue. As the Facebook study on the equals sign found, the number of friends who adopted the photo played a role in whether or not someone would also choose to change their display picture, but so did demographic characteristics, such as age, gender, education, and factors relevant to marriage equality, such as religion.

As aforementioned, not all spaces are created equal. Assuming everyone has the same amount of political risk when adopting a given issue assumes that your entire audience is all on the same playing field. When you can have scenarios where one group needs to actively check out for self-care and the other has the luxury of becoming incredibly woke because the issue is for them, at most, performative, finding the tipping point is much more nuanced than simply attempting to get people onside.

This isn’t to say that you can’t use social media to do this — this is to say that you need to consider which group your message addresses, whether intentionally or not, the most: Performative support isn’t the kind that correlates to action, and worse, it’s the kind that can alienate real supporters from your efforts. If your issue is high-stakes for you, realizing that it could be high stakes for others is the minimum level of consideration you should give when using means to persuade them to publically support your cause. When people are actively avoiding engaging in issues to avoid being part of one group or to engage in a level of self-care, there’s an added level of sensitivity required in what you’re saying and how you’re saying it.

To take it back to Gawker — Gawker was unafraid to challenge the status quo, the powerful, and it took chances on content, sources, and the types of stories it ran. Much of its content was controversial, but it also gave a voice to a lot of people who wouldn’t have had one otherwise, and for that it will forever hold a place within the history of the Internet. And in the end, to the dismay of many, that level of confidence and brashness didn’t survive and it was forced out. Although it’s now bankrupt, Gawker Media as a whole will continue through its affiliate sites. But the brand and the ideals of gawker.com have been effectively shut down. The end of Gawker is bad for many reasons, implications for free speech being one of them. As much as the Internet seems like a free-for-all, it’s still worth asking who has room to participate and what’s at stake for them if they do.