Sexual Harassment in the Workplace: The Public’s Perspective

Download the report here: Report on Public’s Perspective of Sexual Harassment in the Workplace

We are in the midst of a transformative moment for the workplace; the beginning of a cultural zeitgeist that approaches harassment and misconduct in a professional environment in a profoundly different way than it ever has before. It is difficult to watch television, open a magazine, or read a newspaper without being inundated with stories of inappropriate behaviour in the workplace. The shocking fall of Harvey Weinstein was only the beginning, as the #metoo and #timesup phenomena have swept the globe with ever-increasing momentum.

It is a moment that has set into motion significant change and will, hopefully, have lasting effects on the way that people interact with each other in the workplace. It also brings with it major implications for organizations, and the public’s expectations of their processes and procedures in the face of these types of high-profile challenges.

While many organizations have taken steps to shape the culture of their workplaces to be positive, inclusive and free from harassment, it is naive to think that employers can, in all cases, control the behaviour of employees as there will always be those who engage in behaviour that contravenes the values of the organization.

What can be controlled, however, is the preparation for and the management of these challenges when they arise.

Public and media expectations of an organization’s response have evolved and grown, and are under more acute scrutiny now than ever before. There is little public sympathy for a slow or indecisive response when allegations surface regarding inappropriate behaviour within an organization. Organizations that are perceived to be delaying or protecting wayward employees are at an increasing risk of receiving significant negative attention on social and traditional media, harming their long-term reputation. They also risk lasting harm to their workplace culture and employee morale, and put themselves at substantial risk in both the court of public opinion and a court of law.

However, there has been speculation that the expectations of media are out-of-line with that of the public. Leaders of organizations have wrestled with questions of morality, and the importance of protecting their organization. The absence of data meant that organizations were acting blindly, taking or delaying action based on instinct rather than taking an evidence based approach.

At Navigator, we believe in always taking a research-guided approach to solve challenges. When managing issues that capture the public attention, it is critical that organizations understand the expectations of the public.

With this in mind, to better understand how Canadians perceive these issues and how they prefer to see them addressed, Navigator undertook a major national survey that investigates the attitudes and beliefs of the public. The survey examines a number of issues, and uses a specialized approach to understand whether some of the received wisdom that exists on the issue is correct.

The results provide a comprehensive and fascinating understanding of the landscape, and should be used as a tool for organizations to understand how to create a safe environment internally, to manage its approach to challenges, and to protect itself from reputational damage should an issue emerge.

It is vital that leaders of organizations understand and manage this issue, for the good of their employees and for the protection of the organization. This survey is a vital and valuable tool in that understanding.

Methodology

The survey was conducted among a national proportionate sample of 2000 Canadians.

The study was conducted using an online methodology and was undertaken from February 12 to 20, 2018. Respondents were able to complete the survey in the language of their choice: English or French.

Quotas were instituted for region, age and gender to ensure that the sample reflects the characteristics of the Canadian population based on recent Statistics Canada data. Further, weights were applied to ensure that the educational level of respondents reflects Statistics Canada data.

Responses may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Understanding of Sexual Harassment in the Workplace

The legal definition of sexual harassment is defined in legislation differently across jurisdictions, but those definitions rarely align with public perceptions of sexual harassment. For instance, in Ontario, which is the province in Canada with the most wide-ranging definition of sexual harassment, the legislation describes sexual harassment as “engaging in a course of vexatious comment or conduct against a worker in a workplace that is known or ought reasonably to be known to be unwelcome.”

This wide-ranging definition leads to significant confusion when used in real-world situations. Situations involving harassment, for example, often involve the harasser being unaware of how their actions are perceived. The past year has provided many examples of this; rarely, it seemed, did a statement from an accused not include an explanation that they did not understand their behaviour to be harassment at the time. Such confusion can be deeply challenging for organizations attempting to appropriately and fairly adjudicate such situations.

This confusion is perhaps best illustrated by the fact that the public’s understanding of sexual harassment varies greatly. When asked to self-assess their understanding of sexual harassment in the workplace, 66% of Canadians describe themselves as having a good understanding; only 7% describe themselves as having a poor understanding.

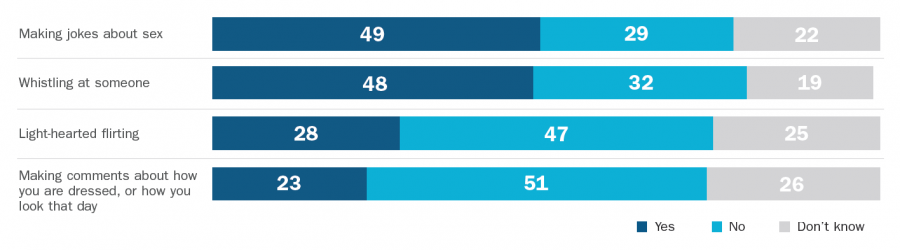

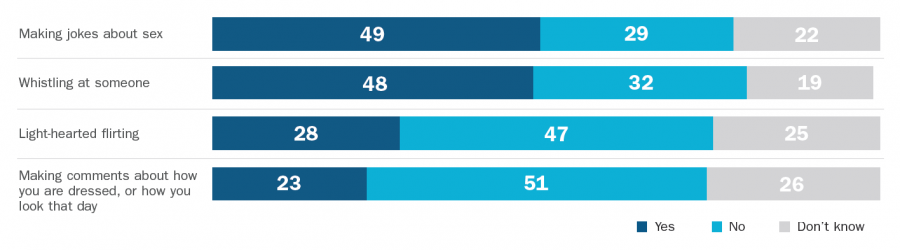

However, when asked to describe whether an action is sexual harassment or not, views are far from aligned on a number of issues.

Perceived Seriousness and Prevalence of the Issue in Canada

During the media frenzy of the #metoo moment, prominent commentators have questioned whether the intensity of public concern is aligned with that of journalists.

When asked, 82% of Canadians describe the issue as a serious or very serious issue, with only 18% believing it is not serious.

Notably, more women (88%) than men (74%) feel it was a serious or very serious issue.

To understand the intensity of Canadians’ belief that sexual harassment is a serious issue, Navigator asked those participants to rate a variety of well-known but unrelated issues. Sexual harassment in the workplace ranks along other hot-topic issues, including the signing of NAFTA, the legalization of cannabis, and volatility in the stock market.

Further, two-thirds of Canadians express the belief that all or most Canadian companies struggled with issues of sexual harassment.

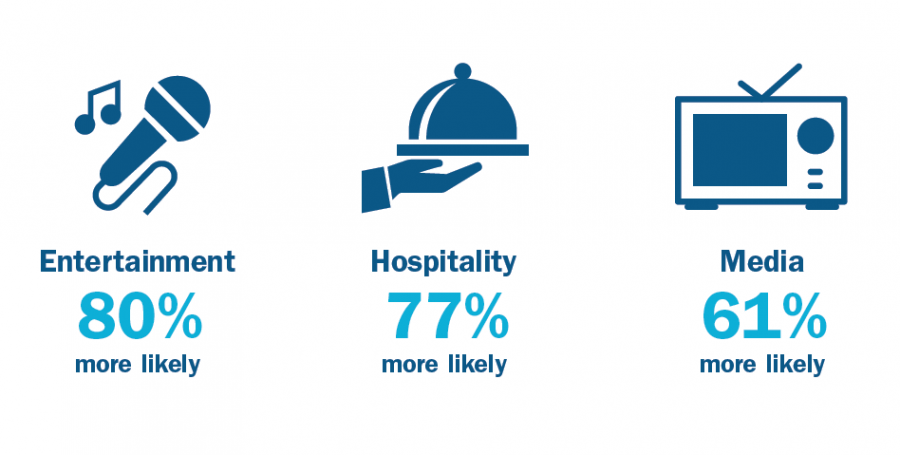

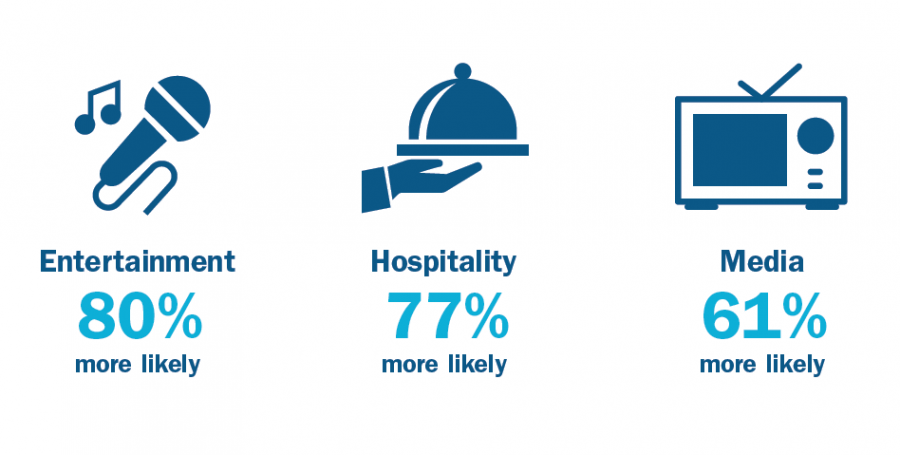

Often, when managing public affairs issues, companies must overcome narrative challenges. If a pattern of behaviour that is unacceptable in the eyes of the public becomes evident, a company’s credibility is tarnished and their ability to counter public criticism is limited. It is with this in mind that Navigator sought the opinions of Canadians on their assessment of industry. Navigator tested more than 18 different sectors for their credibility on this issue.

Participants believe that organizations in the entertainment industry, hospitality industry, and in the media are most likely to be hotbeds for sexual harassment.

Prevalence of the Issue in the Workplaces of Respondents and Evaluations of Current Employers

It is vital that leaders of organizations create a safe space for employees. Not only does creating such an environment help the organization thrive, but it allows leaders to deal with issues openly and rapidly, preventing them from sustaining public criticism. A surprisingly high proportion of employed Canadians – 2 in 5 – feel that sexual harassment is a serious problem in their own workplace.

40% of Canadians say there is some or a lot of sexual harassment in their workplace.

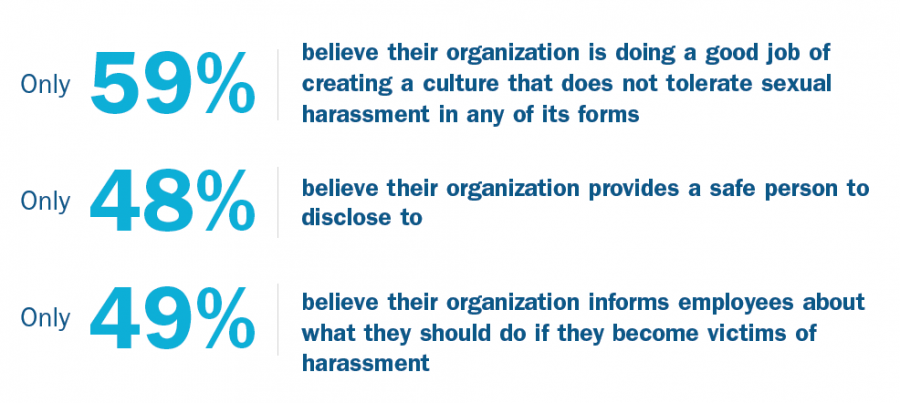

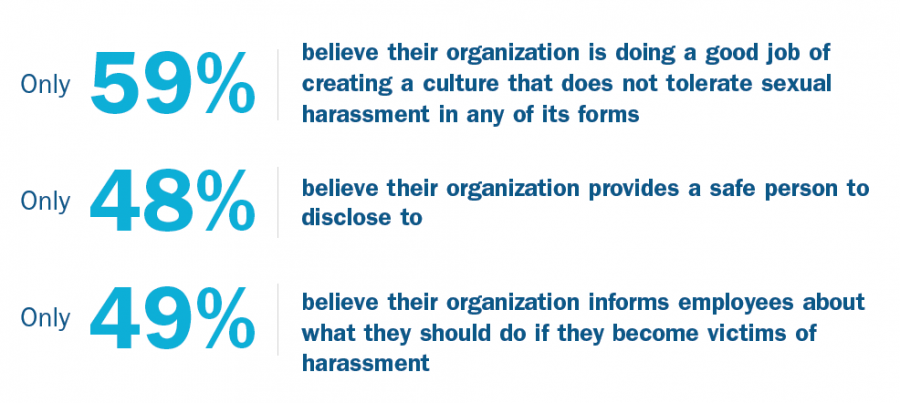

When tested on a variety of issues, Canadians expressed ambivalence about the internal policies of their own organizations. Many feel that their organization has simply not done an adequate job, while fewer than a quarter answered that their organization was doing a “very good job” on a variety of metrics. Those metrics included whether the company has in place appropriate policies, whether they provide a safe culture, and whether they

do an appropriate job of informing employees.

Incidence of Personally Experiencing Sexual Harassment in the Workplace

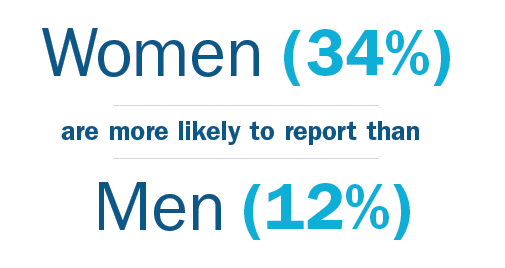

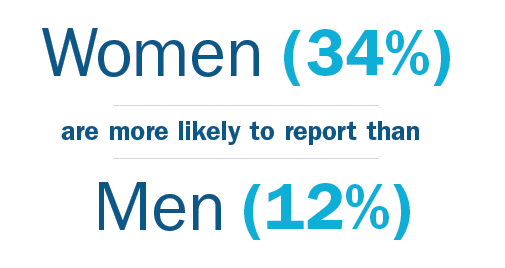

The prevalence of sexual harassment in the workplace is another metric that was tested in the survey. Approximately 24% of Canadians reported that they had experienced sexual harassment in the workplace. Women are considerably more likely than men to report that they have been victims of harassment.

Problematically, of those who report that they have been sexually harassed in the workplace, nearly 2 in 5 report that the sexual harassment stemmed from a person who had direct influence over their career.

Perceptions of Management

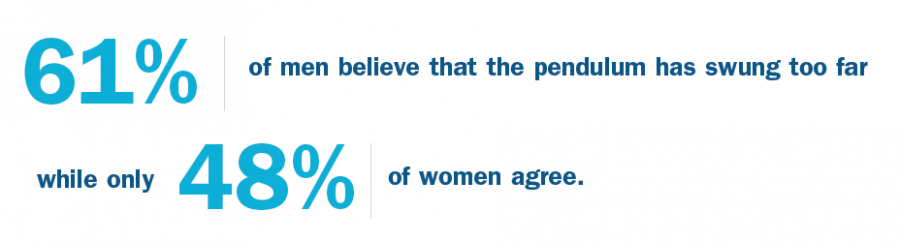

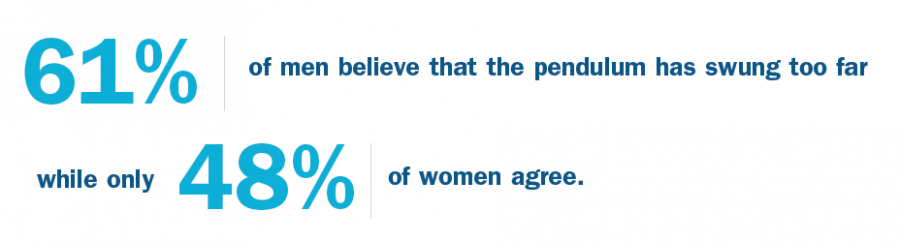

When it comes to how Canadians perceive the management of the issue, the opinion of Canadians is more nuanced. For instance, while 71% of Canadians feel that it has taken far too long for the problem of sexual harassment in the workplace to be taken seriously, when asked if they believe the pendulum had swung too far, 54% agree with only 18% disagreeing.

This question once again demonstrates a gender disparity:

Takeaways for Organizations

It is evident that Canadians believe that sexual harassment is an issue, and one that must be dealt with appropriately by organizations. Their expectations and beliefs regarding how organizations must behave will define whether those organizations will survive public criticism.

Organizations must not wait for the challenges to come to them: they must be prepared to manage and deal with issues as they come, and they must act to prevent issues from emerging by creating a safe work environment in the first place.

It is vital that leaders of organizations take steps to create this safe work environment, both to maintain a healthy organization and to prevent themselves from sustaining reputational damage.

Download the report here: Report on Public’s Perspective of Sexual Harassment in the Workplace