- CEOCap

- Jaime Watt’s Debut Bestseller ‘What I Wish I Said’

- Media Training

- The Push Back

- Internship program

- Update Your Profile

- Homepage

- It’s time for a change

- It’s time for a change

- Kio

- Ottawa

- Art at Navigator

- Navigator Limited Ontario Accessibility Policy

- Virtual Retreat 2020 Closing Remarks

- COVID-19 Resources

- Offices

- Navigator Sight: COVID-19 Monitor

- Navigator Sight: COVID-19 Monitor – Archive

- Privacy Policy

- Research Privacy Policy

- Canadian Centre for the Purpose of the Corporation

- Chairman’s desk

- ELXN44

- Media

- Perspectives

- Podcasts

- Subscribe

- Crisis

- Reputation

- Government relations

- Public affairs campaigns

- Capital markets

- Discover

- studio

- How we win

- What we believe

- Who we are

- Careers

- Newsroom

- AI

- Empower by Navigator

- Environmental responsibility

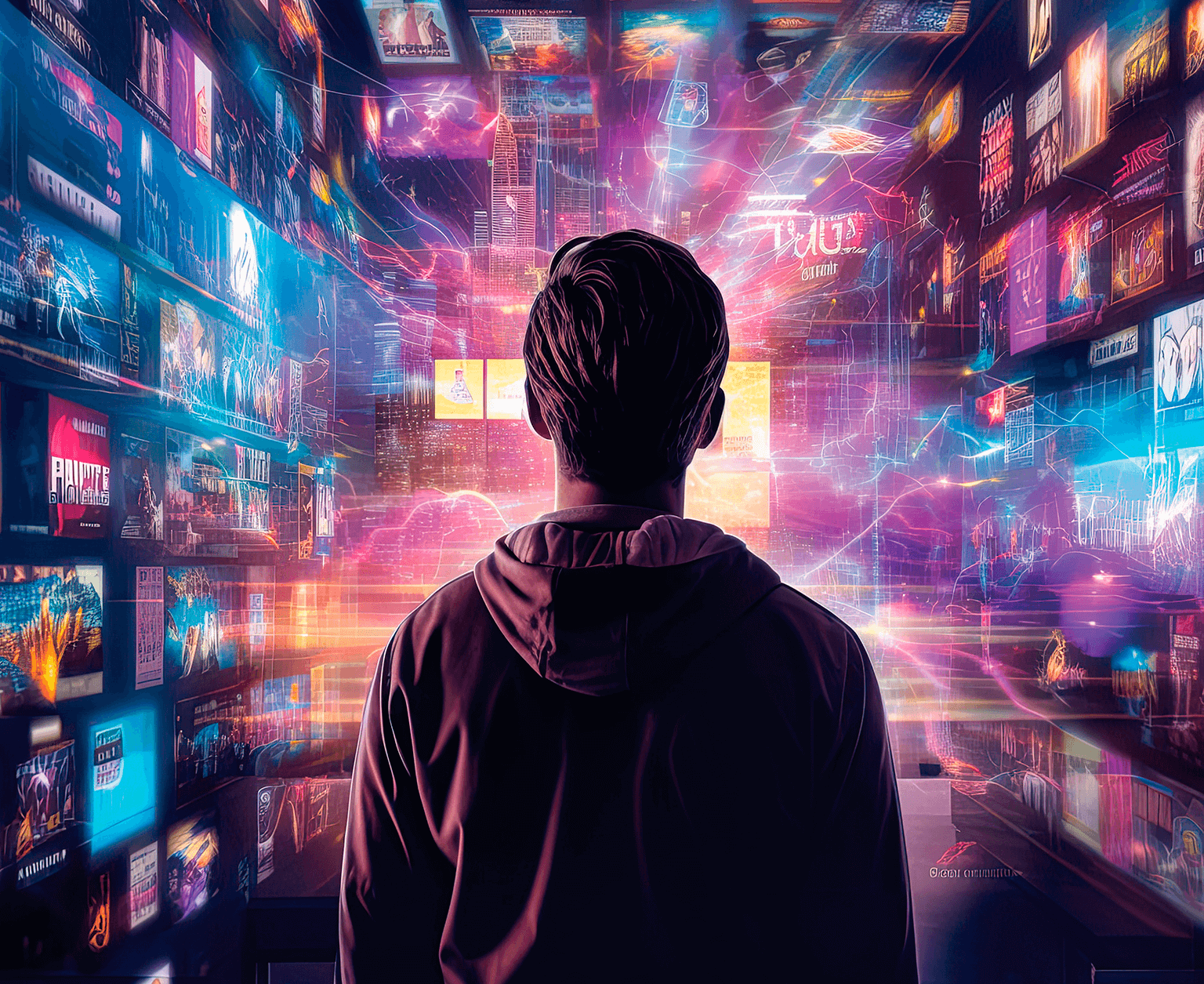

How does a rapidly changing industry cover an even more rapidly changing world?

In the evolving Canadian media landscape, where over the past number of years everything seems to have changed, one can’t help but wonder: have we entered a new chapter or a new book altogether?

The pages of traditional journalism, once neatly bound in print, have transformed into digital scrolls, while the margins teem with voices that refuse to be confined. It’s a story where ink meets pixels, where the old guard contends with the disruptors of the new media order. In short, it’s more War and Peace than Cat in the Hat.

Who better to shed light on this complex and changing story than three of our nation’s most prominent journalists? From the newsrooms of legacy publications to the uncharted territories of Substack, they are the storytellers shaping our understanding of the world. Relishing the opportunity to ask them the tough questions, we inquired about the most pressing obstacles they face, where they believe journalism stands now, and what’s to come. Together, they offer us a glimpse into the metamorphosis of our national “news-scape” — a transformation marked by immediacy, interactivity and, at times, discord.

Welcome to the future of Canadian media.

Vassy Kapelos

Chief Political Correspondent, CTV News

What gives you hope for the future of the industry? What is Canadian news doing well?

My experience during the pandemic really reminded me of the purpose that news can serve in people’s lives, and the sort of appetite that still exists.

I know a lot of people probably think that’s weird because so much negativity towards and about the media was part and parcel of the pandemic. I’m not dismissing any of the criticisms or the rebuttals of those criticisms. But, from a personal perspective, my experience during the pandemic, professionally speaking, I felt as though I had never had such a direct connection or ability to connect [with the audience].

What the government was doing and how it impacted people’s lives was so immediate. So many people were reaching out all the time saying, “Can you ask this? Can you ask that?” It was not performance-based at all. At night I was truly like, “Okay, what do I need to ask in order to help this group of people or that group of people.”

It sounds very Pollyanna, but it wasn’t. People were nervous and worried, and their livelihoods were at stake. I felt like there was a real purpose [in what] I was doing. I know the purpose existed previously, but it was so acute during the pandemic.

The degree to which people relied on us for information and for help was really a stark reminder for me of what we’re there for in the first place, and the need still exists.

Hopefully, there’s not another pandemic, but there are many things that matter to people in their daily lives that the government has some impact on one way or another. People need information, and they come to the media for that information. I take that very seriously. There’s going to be other stuff that happens in the world where people want accurate information and they come to the news for that.

Do you worry that the industry of journalism still maintains public trust?

It’s a good question to ask. I just don’t know if I have the answer. If I absorb every criticism of the media or industry at large, I wouldn’t want to get up and do my job in the morning. I’m able to separate myself and the work I do from the big picture.

I don’t want to sound as though I’m tuning it out, because I’m not. Some of the criticism is bound in people’s experience and I don’t want to dismiss that at all.

From the start of my career, I’ve thought of it as: I have to do the best job possible, have the least bias. I have to be consumed with being accurate and trying to be helpful. Ultimately, I can’t control what everyone else in the industry does, or the way in which everyone out there perceives the industry, but I can control what I do.

Kelly Cryderman

Reporter and columnist, The Globe and Mail

What do you make of the industry as it stands now? How are Canadians consuming their news?

It’s a challenging time, a time of transition.

It’s a time of figuring out a whirlwind of technology that has been thrust upon us in the last 15 to 20 years, and how journalism as a business exists and how our ideas about objectivity, and the things we learned in journalism school, exist in this new world.

I think everybody is adapting to a really rapid pace of change when it comes to social media and what’s available.

I remember my grandfather saying to me, when he was more than 100 years old, “I don’t know about your job anymore because everybody has access to information at their fingertips.” He made this comment having seen a century of change.

What makes you optimistic about the future of the industry? What worries you?

What makes me optimistic is reading, watching and listening to great journalism.

There still are the stories out there that introduce me to a totally new idea or a new concept or highlight a problem in the world that I didn’t know existed. It opens a window to something good happening in the world that I didn’t know existed.

I feel inspired by stories that people are still telling, and also when I get feedback on what I write. When you’re writing to be read, and get feedback on that, good and bad, it’s important because I know people are paying attention.

What makes me hopeful is that I think human beings are inherently storytellers. How we understand the world is through stories, and we will always need to do that, no matter what.

Do you think there’s a place for governments to support journalism financially?

Like a lot of people, I have a natural aversion to governments supporting journalism or getting involved in journalism. But I do think there could be some kind of system in place for some government role that does work. I do believe that, too. I think it’s complicated.

When I look at local journalism, for which I have a large amount of concern, I see a city like Calgary where the paper I used to work for, the Calgary Herald, has a very small number of staff now compared to what it had. I do worry about local journalism, which does matter.

I see the role of foundations in the United States especially, and also here, playing a role in journalism. I do ask the question, if large foundations can play a role in journalism, could governments?

It’s not an area I’ve spent a lot of time focusing on. My natural answer is that I’d rather [governments] not. But I know things are changing.

Justin Ling

Freelance journalist, author of the ‘Bug-eyed and Shameless’

What do you make of the industry in Canada today? How is it changing?

Canadian media was in a tough spot even before the advertising economy sort of tanked. We had gone through mass consolidation of a whole bunch of not super liquid outlets. It made a ton of sense at the time, but in hindsight set us up for a sort of too-big-to-fail situation, right? A small number of players, many of which were ladened with debt without any particular interest, or even in some cases expertise in publishing.

Then there was a real transitional moment where I think everybody kind of thought we would be saved by online media. But just like everywhere else, it boomed and then bust.

I spent four years working for VICE. Thanks to huge investment from Rogers Media, we thought, many thought, we were the future. I was at BuzzFeed for a while. All of these outlets spent big and collapsed spectacularly.

Through all that, we haven’t learned anything. We went through all that and we came out the other end and we still don’t have a plan. We made mistake after mistake. There’s really no country you can point to that’s doing this really well, but I think we’re in a particularly bad spot. We’re right next to a massive media market and we’ve made a whole bunch of mistakes setting up our domestic industry. We have distribution problems. It just leaves us in a spot where we really have no runway left.

What gives you hope?

We still have a ton of great journalists, which is great. The fact that there are thousands of people subscribed to Paul Wells’ Substack is great. The fact that being on the At Issue panel (at CBC News) still makes you a household name is great. We want an industry where people recognize outlets, names and so on, especially as you go to an online economy where everything becomes kind of flat.

The fact that the CBC still manages to maintain its cultural relevance in Canada, the fact that people still trust it, still listen to it, still turn on the television and radio, is really good news.

What worries you?

We’re facing a deeper problem here. There is a revenue problem that’s killing everybody. It’s why Maclean’s no longer does news. The revenue problem is really acute, it’s there. But we also don’t talk about the distribution problem. It’s not just that our outlets are making less money, it’s that fewer people are reading and watching them.

We don’t want to recognize this as a problem because it suggests that Canadians aren’t interested in news, but it’s actually the opposite. More people are reading news more than they ever have. The issue is they’re not going to get that news in the place where we want them to.

We’re in a crisis right now and we don’t know how to solve it.

I’m not sure we’re trying hard enough to solve it, to be really honest.

Do you think there’s a place for a public broadcaster?

My take is that the CBC probably needs more money, not less, but we need to talk seriously about what the CBC’s mandate is.

Is the CBC’s mandate to run Family Feud Canada? I don’t think so. My take is that we’re wasting a lot of money pursuing projects at the CBC that seem more designed to pick up advertising revenue, and, frankly, it’s hard to blame them.

Is this the BBC, or are we trying to push the CBC towards eventual privatization? We have to make that decision at some point. We’re still like all things Canadian: we’re trying to pursue a middle road that gives us the worst of both worlds.

I’d love to see a CBC that recognizes that the client, and local news coverage is acute and therefore we need to put more money into it.

I think if we can elucidate what the CBC’s role is more effectively, it will be a lot harder for people to call for it to be abolished. But at the same time, we also have to recognize that the CBC is not the voice of God to all people. We need other outlets.