- CEOCap

- Jaime Watt’s Debut Bestseller ‘What I Wish I Said’

- Media Training

- The Push Back

- Internship program

- Update Your Profile

- Homepage

- It’s time for a change

- It’s time for a change

- Kio

- Ottawa

- Art at Navigator

- Navigator Limited Ontario Accessibility Policy

- Virtual Retreat 2020 Closing Remarks

- COVID-19 Resources

- Offices

- Navigator Sight: COVID-19 Monitor

- Navigator Sight: COVID-19 Monitor – Archive

- Privacy Policy

- Research Privacy Policy

- Canadian Centre for the Purpose of the Corporation

- Chairman’s desk

- ELXN44

- Media

- Perspectives

- Podcasts

- Subscribe

- Crisis

- Reputation

- Government relations

- Public affairs campaigns

- Capital markets

- Discover

- studio

- How we win

- What we believe

- Who we are

- Careers

- Newsroom

- AI

- Empower by Navigator

- Environmental responsibility

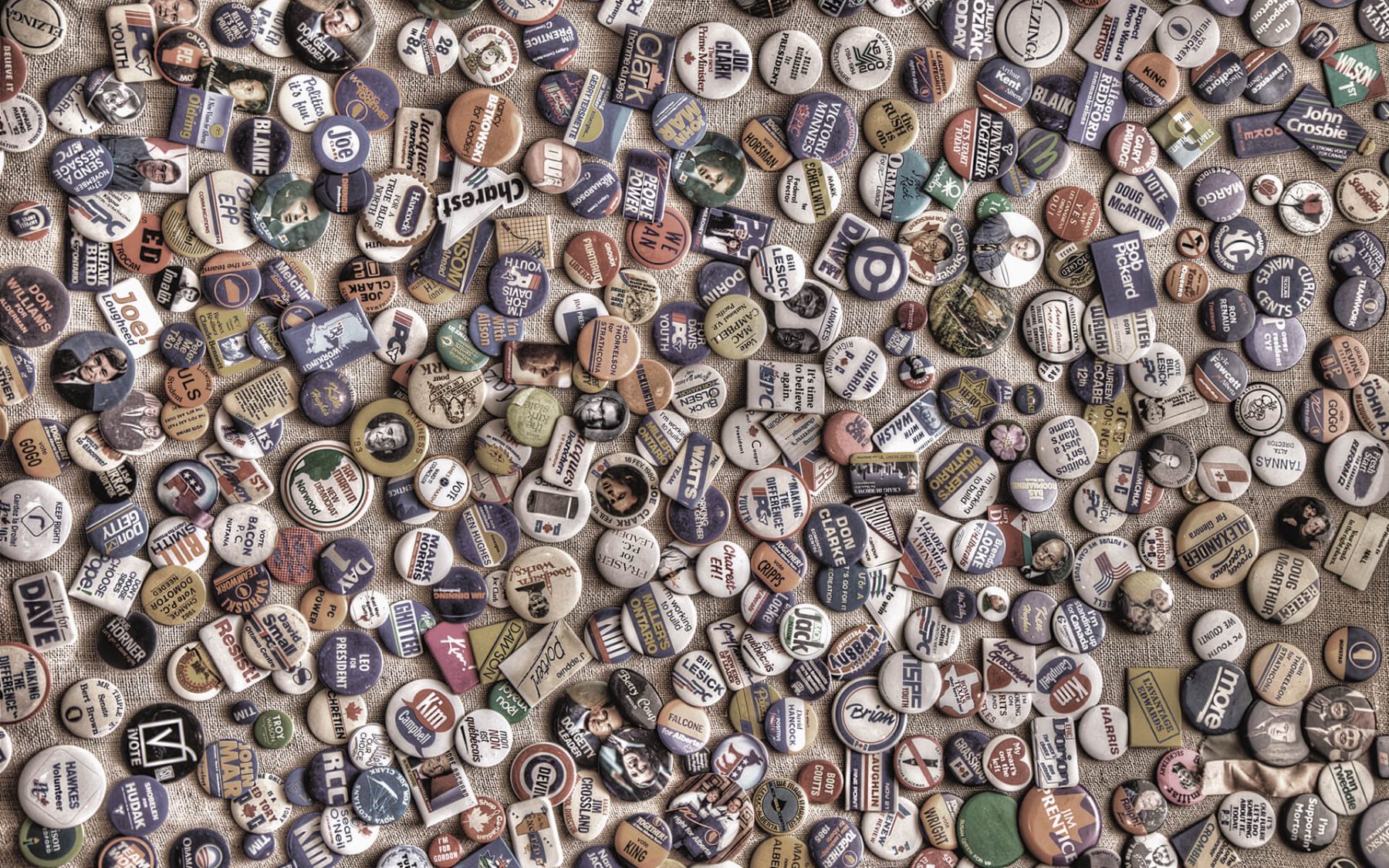

Political campaigns have become more sophisticated with the advent of technology and its application. One constant, however, is the importance of the campaign veterans who have loved, lost, won and lived to fight another day. Navigator Managing Principal, Randy Dawson, is one of the most seasoned — and most successful — campaigners in Canada

I worked on my first political campaign in 1978. I was 18 years old, and the candidate, Rollie Cook, was 26. He was seeking the provincial Progressive Conservative nomination in the newly created riding of Edmonton Glengarry.

In those days, there were no computers, no email, no cellphones. People still opened their doors if you knocked. And they answered their telephones when they rang. Lists were typed out on paper. And hundreds of volunteers came together to do the work.

Even 15 years ago, email and cellphones were just starting to become more common. Some computers were used for rudimentary list management, but when it came to targeting voters, we manually searched through books of census data, picked up land-line phones and knocked on doors.

We’ve gone from a 24-hour news cycle with CNN to a 24-second news cycle with Twitter. It’s not just the issue of speed trumping accuracy, but it makes it much more challenging to cover big, complex issues in a meaningful way.

Since then, however, the pace of change in political campaigns has accelerated rapidly.

Technology is the most obvious driver of that change. It’s now used to target voters and to constantly refine campaign strategy using data that’s collected on an ongoing basis through social media and the use of specialty software.

The application of advanced technology has significantly diminished the reliance on volunteers — although their retreat was already underway. In general, Canadians are not only busier, but the volunteer base is spread more thinly because more sectors than ever rely on volunteers.

Replacing those volunteers is an emergent professional management caste, specializing in voter mobilization. While many of these political experts reside within party organizations, the ranks of third-party contractors is also growing — a trend that’s migrating from the U.S. to Canada.

These professionals have become essential because of their specialized skill set and also because fixed election dates have extended the length of campaign preparation time. Instead of six months of campaigning ahead of an election, it’s more typically a year. And that’s more than most civilian volunteers could handle.

Financing is another aspect of traditional campaigning that has radically changed. The move from large, single donations to multiple individual contributions is partly a function of technology. Certain programs allow parties to narrowly target contributors based on the resonance of specific issues with their personal interests and beliefs. Financing has also changed because of new rules and attitudes.

Even where corporations are still free to contribute to campaigns, some companies consider political donations an unacceptable use of shareholder capital. The direct appeal for financial support from individuals gained momentum in Canada with the emergence of the Reform Party movement in the 1990s. Reformers had no established network, no big backers, no institutional framework. They had to learn how to raise money directly from supporters — and how to find those supporters. It was an innovation born of necessity.

Another key difference in campaigns is the role of media. Where 15 years ago we worried about media concentration, now the issue is extreme fragmentation. It’s hard to know whom you’re talking to or dealing with when you try to communicate your message. Then there’s the issue of speed. We’ve gone from a 24-hour news cycle with CNN to a 24-second news cycle with Twitter. It’s not just the issue of speed trumping accuracy; it makes it much more challenging to cover big, complex issues in a meaningful way.

In the end, politics and campaigns haven’t fundamentally changed in 15 years. There’s still a bus, there’s still a plane, there’s still a war room — though now everything is monitored around the clock.

Furthermore, today — as it was 15 years ago or three thousand years ago in the days of Cicero — the best way to reach voters is through direct personal contact. We may be doing that in new ways, but the reality is that people want to engage. And campaigns are all about finding the best ways to do just that.

Of the many campaigns I’ve worked on over the years, I have to say my absolute favourite was Jim Prentice’s 2003 federal Tory leadership campaign. It was a real underdog endeavour and we had to slog hard, constituency by constituency, dollar by dollar.

That said, the calibre of the people who stepped up to participate, especially at the convention, was absolutely remarkable. It really was an A-team.

It was all clearly chronicled in the convention coverage: the suspense, the momentum, the tension. In the end, we lost. But it was all redeemed by the fun, the excitement and the electricity.

This campaign is also my favourite because of the issue at its heart. The whole focus was on uniting the Conservative Party and putting an end to all the fighting that had been going on for too long.

In my mind, Jim Prentice came the closest to articulating a vision for a united party. And I have never lost sight of how special — and how important — that process was. And the legacy the debate created.